MADISON Strategic Plan

Part A. Background Report

MADISON Strategic Plan

Part A. Background Report

May 2018

Prepared by Randall Gross / Development Economics

Through a grant from The Memorial Foundation For All Together Madison and the Madison Community

NASHVILLE: 4416 Harding Place, Belle Meade 37205. Tel 202-427-3027 / Rangross@aol.com

WASHINGTON DC: 2311 Connecticut Ave Ste 206 20008. Tel 202-427-3027. Fax 332-1853. Rangross@aol.com AFRICA: African Development Economic Consultants (ADEC). 27-11-728-1965. Fax 728-8371. Randall@ADEC1.com UK: 118 Hampstead House, 176 Finchley Road, NW3 6BT London. Tel 44-79 0831 6890. rangross@aol.com

INTRODUCTION

A Strategic Plan has been prepared for the community of Madison on behalf of Madison’s residents, businesses, institutions, and other key stakeholders. This plan is the initiative of a grassroots, community-based coalition (All Together Madison ATM) in collaboration with other Madison organizations and Metro Nashville Government agencies. Funding for this initiative was secured through a grant from the Madison-based Memorial Foundation and from two private contributors. Members of ATM and a project steering committee helped guide the process undertaken by the consultant.

Purpose

Madison is part of Metro Nashville. If Madison were incorporated as a municipality, it would be the 17th largest city in Tennessee, with more than 40,000 residents. Residents see a need for economic development and revitalization, while at the same time, preserving Madison’s relative affordability in the face of rapid growth in the broader Nashville region. Previous plans and studies in Madison examined physical issues and provided infrastructure and development recommendations. However, they lacked the benefit of market and economic analysis to help underpin strategic recommendations.

The Strategic Plan examines socio-economic issues and forecasts real estate market potentials. Based on in-depth analysis and community stakeholder guidance, opportunities are identified for revitalization and development while enhancing the quality of life for Madison residents in all income levels.

Components and Structure

In essence, this plan presents a Strategy for the Revitalization and Economic Development of Madison. It includes an assessment of existing conditions, key strengths and challenges. The plan also presents findings from economic and real estate market analysis forecasting Madison’s potential in terms of market-rate and affordable housing, office space, retail/commercial space and industrial uses. Community visioning and engagement fully informed the recommendations. Strategies are developed for marketing and identity branding, development, organizational structure, financing, management, community economic development and other components. An Implementation Action Plan provides a point-by-point guide to implementation with specific actions for funders, non-profit organizations, government agencies, residents, businesses, property owners, and investors.

It should be noted that this is not a physical development plan or master plan for development of Madison. Nor does it provide a zoning plan or proposal that requires approval by Metro Government or its Planning Commission. This plan is not funded by Metro Government but should help inform Metro agencies and provide useful information to guide investment. This strategy is not a plan for any specific organization or group of people. It is intended for use by all of Madison’s residents, businesses, property owners, investors, institutions, and others.

Report Structure

The Strategic Plan comprises of three separate volumes (“parts”) and an Executive Summary. Part A: Background Report presents information gleaned from community stakeholders and background research on the community’s history, challenges, opportunities, existing conditions, and competitive advantages. Section 1 of the Background Report provides an Existing Conditions Assessment while Section 2 provides a summary of input from stakeholder meetings, interviews, and presentations.

Part B: Market Analysis Report, provides a summary of findings on the existing and potential market for office, industrial, residential and retail uses within the Madison study area. Section 1 presents findings on Office, Section 2 Industrial, Section 3 Residential, and Section 4 Retail. An overall summary of market findings is provided in the final section of this Part B Report.

Part C: Strategic Implementation Plan. Part C provides the recommended strategies for economic development and revitalization of Madison, relating to marketing and identity branding, development, organizational structure, financing, management, community economic development and other components as noted earlier. Part C also provides a 3-5 year Implementation Action Plan matrix that identifies the specific tasks and timetables, assigns responsibility, and generates indicative costs and proposed funding sources for each of the listed tasks.

Acknowledgements

The consultant wishes to acknowledge the tireless grassroots efforts of the community and members of All Together Madison, under the leadership of Sasha Mullins-Lassiter and Mark North. Also recognized are the contributions of the various Madison organizations including the Madison-Rivergate Chamber of Commerce, Discover Madison, Madison 360, and others as well as churches, schools, and other institutions. The work could not have been possible without the financial contributions and support of The Memorial Foundation and several private individuals. Finally, the many residents, businesses, property owners and investors in Madison who participated in this strategic planning process over a two-year period provided the vision, input, and inspiration for recommendations contained herein. Key acknowledgements are detailed below.

Initiative

Initiative

- All-Together Madison (ad hoc community-based coalition)

Funding

- The Memorial Foundation: Scott Perry, President

- Anonymous and Ross Cortese, private contributors

Strategic Steering Committee

- Madison Residents

- Representatives of key Madison organizations & funders

- Civic & religious institutions

- Business and real estate interests

- Ex Officio: Elected officials and Metro agency staff

Consultants

- Randall Gross / Development Economics

- Ben Johnson Illustrations (Conceptual renderings)

Advisory, Design, and Logistical Support

- Gresham Smith

- Nashville Civic Design Center

Madison Organizations

- Discover Madison

- Madison-Rivergate Chamber of Commerce

- Madison 360

Political Representatives

- Anthony David, Metro Council District 7

- Brenda Haywood, Metro Council District 3

- Doug Pardue, Metro Council District 10

- Bill Pridemore, Metro Council District 9

- Nancy VanReece, Metro Council District 8

- Jill Speering, School Board District 3

- Bill Beck, Tennessee State Representative

- Brenda Gilmore, Tennessee State Representative

- Thelma Harper, Tennessee State Representative

- Bo Mitchell, Tennessee State Representative

- Steve Dickerson, Tennessee State Senator

- Jeff Yarbro, Tennessee State Senator

Metro Government Agencies

- Mayor’s Office

- Metro Arts Commission

- Metro Development & Housing Agency

- Metro Planning

- Metro Public Works

- Metro Schools

- Metro Transit Authority

Section 1. EXISTING CONDITIONS ASSESSMENT

This section provides findings from an assessment of existing physical, demographic, and socio-economic conditions in Madison. A discussion of Madison’s location, transportation access, history, culture, economy, demographics, and physical conditions help provide context for economic development and for addressing key issues identified as part of this strategic planning process. A site analysis also provides input to market and economic analyses discussed in the Part B Report.

Location and Study Area

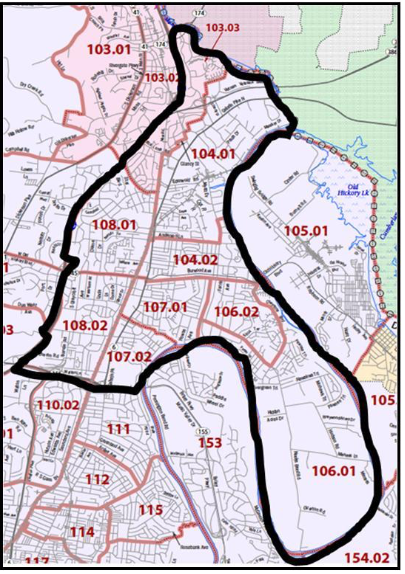

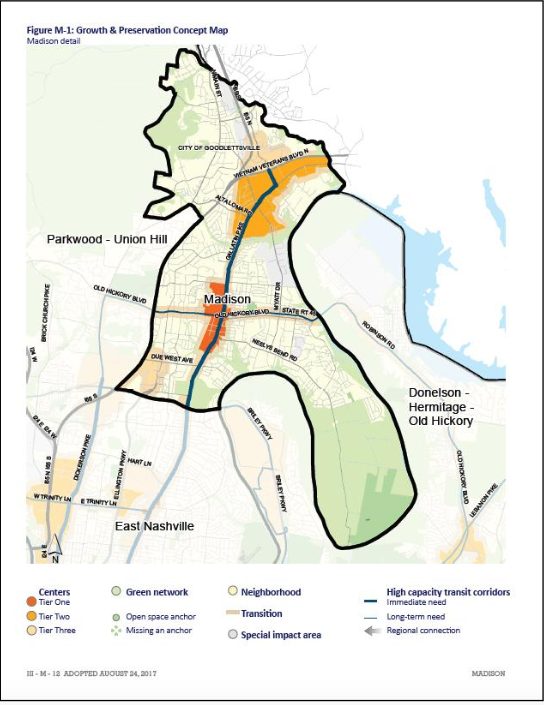

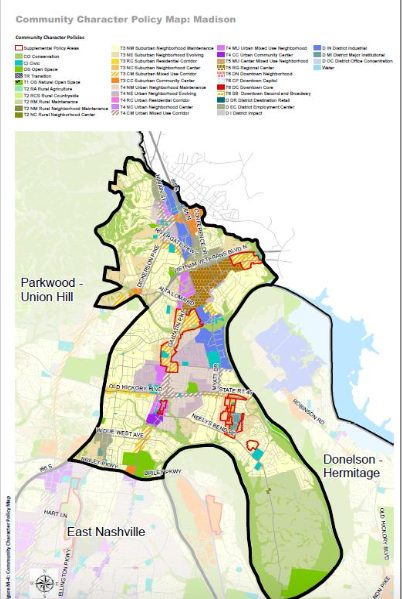

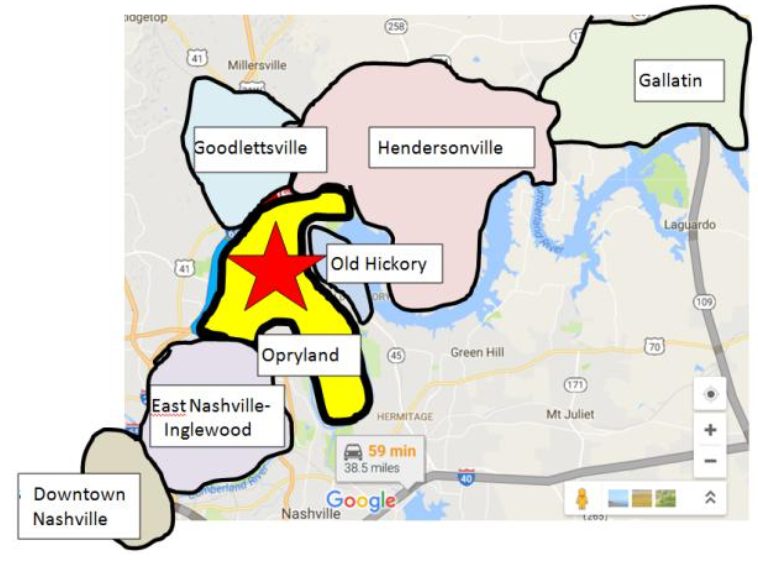

For the purposes of this Strategic Plan, Madison was defined by All Together Madison (ATM) as the portion of Metro Nashville bound on the south by Briley Parkway, on the east by the Cumberland River, on the north by Sumner County, and on the west by I-65. In addition, some consideration was also given to areas west of I-65 to Dickerson Pike.

For assessment of the demographic base, the Study Area includes Census Tracts 103.03, 104.01, 104.02, 106.01, 106.02, 107.01, 107.02, 108.01, and 108.02. Tract 103.03, which lies east of I-65, is a small portion of the City of Goodlettsville that includes RiverGate Mall. Much of Madison also correlates to the boundaries of Zip Code 37115. Overall, this area represents a significant portion of Metro Nashville-Davidson County

Political Boundaries

Madison is an unincorporated place that forms part of Metro Nashville. As such, it has no independent municipal government functions, despite its large size and distinct history as a community. In addition, Madison is represented by no less than five (5) council seats in the Metro Nashville Council, so its local political representation is highly disaggregated. Further, four of these five council districts cover neighborhoods outside of Madison, so they are not dedicated to solely represent Madison’s interests at Metro Government.

- District 7 includes portions of East Nashville, Inglewood, and a small part of Madison east of Gallatin Pike.

- District 8 includes Inglewood and Madison, west of Gallatin Pike.

- District 9 includes the Neely’s Bend and Myatt Drive portions of Madison, east of Gallatin Pike. This is the only Council District located wholly within Madison.

- District 10 includes the northern portion of Madison-RiverGate, as well as Goodlettsville and Ridgetop.

- District 3 includes the Bellshire area west to Whites Creek and north to Ridgetop. While not technically within the Study Area, some associate portions immediately west of I-65 and north of Old Hickory Boulevard with Madison.Downtown Madison is split between Districts 8 (west of Gallatin Pike), 9 (east of Gallatin Pike, north of Neely’s Bend), and 7 (east of Gallatin, south of Neely’s Bend). This political divide adds to the challenge of developing and implementing a comprehensive vision for downtown Madison.

Service Area Boundaries

Portions of Madison that were formerly located within Metro’s General Services District (GSD) were recently added to the Metro Urban Services District (USD). The USD provides a higher level of urban services including trash pickup, sidewalks, street lights, sewer, and stormwater service. While much of Madison already had some of these services, the extension of USD into the area formalizes maintenance and budgeting for these services. That being said, some portions of Madison still reside outside of the USD, including most of Neely’s Bend (southeast of Larkin Springs), RiverGate (north of Dry Creek), and Graycroft (north of Apple Valley Road/1-Mile Parkway). On the west side of I-65, the USD extends only to Old Hickory Boulevard. In general, the USD includes most of Madison, aside from Neely’s Bend and RiverGate.

Neighborhoods

Madison is a broad geographic area that includes a number of individual neighborhoods, subdivisions and multi-family or senior housing developments. Google Maps identifies the following “neighborhoods” in Madison, although some are merely names on the map:

Walton Oaks, Fawnwood, Ellington Place, Oakland Trace, Oakland Acres, Imperial Manor, Pleasant Acres, Holiday Hills, Blair Estates, Blair Heights, Hickory Gardens, Heritage House, Williams Valley, Haven Acres, Morning View, Heritage Square, Castle Grove, Bonnie Brae, Primrose Acres, Primrose Meadows, Graycroft/Graybrook, Alta Loma, Montague, Chippington Towers, Berkely Hills, West Montague, Maybelle Carter, Falcon View, Covington Place, Madison Park, Crittenden Estates, Robin Hood, Forest Park, Lanier Park, Rothwood, Rainbow Terrace, Madison Heights, Kingsway Green, Arrowhead Estates, River Retreat, Cumberland View Towers, Cheyenne Trace, Heron’s Walk, Meadow Bend, Candlewood, Schoolside Heights, Canton Pass, Cumberland Station, Neelys Bend Villas, Kimbolton, Marlin Meadows, Nashwood Park, Rio Vista, Archwood Acres, DuPont Avenue, Kennaston Estates, Madison Park, Woodlawn Estates, Lamplighter, Amqui Place, Cedarwood Courtyard, Shannon Place, Oakwood, Cumberland Bend, Eastlawn, Edgemeade Farms, Crestbrook Meadows, Edenwold City, Harbor Village, Enclave at Twin Hills, Shepherd Hills, Carestone, Churchill Crossing, Bristol Park at Riverchase, and Mansker Meadows.

Organizational Structure

Because Madison does not have its own local government structure, and its representation in the Metro Council is highly disaggregated, local non-profit organizations that represent Madison’s interests thereby become more relevant and important to ensure that Madison retains some control over its future. Despite the presence of active organizations in the past (Chamber of Commerce, Pro Madison, Madison Merchants’ Association, etc), the area today lacks a strong and cohesive network of organizations with the capacity, mission, or structure to implement critical projects or programs. However, there are several organizations with impassioned leadership and a renewed sense of purpose to help revitalize the community. These organizations include the following:

Madison-Rivergate Chamber of Commerce

The longest-running of the local organizations, the Madison-Rivergate Chamber of Commerce has worked for decades to promote Madison as a center for business and commerce. The Chamber, which is registered as a 501(c)6 has recently undergone a transformation with the departure of its long-term director under a cloud of controversy. A new Executive Director has been appointed by the Chamber Board to re-establish a positive image for the Chamber and strengthen its mission in the community. Ultimately, as a Chamber, that mission relates primarily to representing and promoting Madison’s local businesses. The Chamber also brings residents and businesses in Madison together through annual events that celebrate the community’s heritage.

Discover Madison (Amqui Station)

State funding for restoration of historic Amqui Station resulted in the establishment of Discover Madison, an organization charged with maintaining the facility. The mission of Discover Madison is also oriented to attracting visitors to the station and to Madison, and educating residents and visitors alike on Madison’s unique history. This organization has also emerged from a recent transition, with the departure of its director and re-establishment of its board.

All Together Madison

All Together Madison (ATM) is essentially an “ad hoc” group established by a community activist to help guide this Strategic Plan. The group has also become a sounding board for various community engagement processes. ATM has no legal structure or governing board, no set mission or strategic plan. But ATM has also accomplished a great deal in a short time for a group without any legal designation.

Madison 360 & Other Business Associations

Madison 360 is another group without any legal status but has been successful to date in communicating with local businesses and bringing them together for networking and support. Several other ad hoc groups have formed or are also forming in Madison, primarily to represent businesses.

Fifty Forward

Fifty Forward is a regional service provider for adults 50 years and older, offering innovative programs and services through its Madison Station Active Lifestyle Center, located adjacent to Amqui Station at 301 Madison Street. Programs include continuing education, wellness, Living at Home services, performing arts, travel, recreation activities and other services.

Neighborhood Associations

There are a number of existing neighborhood-based organizations including neighborhood watch groups as well as homeowners associations and organizations with a broader purpose of representation and neighborhood improvement. Among the organizations identified based on information from the Nashville Neighborhood Alliance are the following:

Neighborhood Organizations & Homeowners Associations

- Arrowhead Estates Neighborhood Association

- Bonnie Brae Subdivision Community Council

- Candlewood Homeowners Association

- Harbor Village Homeowners Association

- Heritage Square Homeowners Association

- Montague Neighborhood Association

- Neely’s Bend Neighborhood Association

- Shepherd Hills Neighborhood Association

- Walton Oaks Neighbors

Apartment Resident Associations

- Alta Loma Apartments

- Heritage House Apartments

Neighborhood Watch Groups

- Amqui Station

- Crestview Meadows Condo

- Cumberland Station

- East Madison

Transportation Access & Exposure

Madison is centrally-located within the northern half of the Nashville Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), with excellent local and regional access via limited access routes (Interstate 65, Briley Parkway, Ellington Parkway, Vietnam Veterans Parkway) and major arterial thoroughfares (Gallatin Pike (U.S. Highway 31E), Old Hickory Boulevard (State Route 45), and Dickerson Pike (U.S. Highway 41). Good local access is also provided via Neely’s Bend Road, Myatt Drive, Graycroft Avenue, Saunders Avenue, and Due West Avenue.

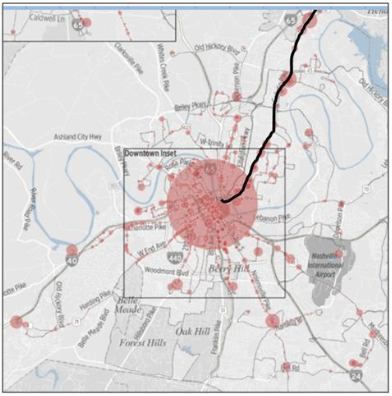

Commuting Distances

Downtown Madison is just 9.5 miles or 18 minutes from Downtown Nashville, making it a desirable location for commuters as well as for residents accessing downtown restaurants and entertainment. Areas on the southern border of Madison near Nossi College of Art are located only seven miles or 10 minutes from Downtown Nashville. Madison is 15 minutes (12 miles) from Nashville International Airport, 16 minutes from Hendersonville (8 miles), and just 11 minutes (5 miles) from the Grand Ole Opry House, Opry Mills, and the Opryland Hotel & Convention Center. Thus, the community is very accessible and proximate to several major employment nodes in the region.

Traffic and Exposure

Interstate 65 in Madison carries 113,000 to 162,000 vehicles per day, according to TDOT’s 2016 Average Daily Traffic (ADT) counts. Thus, the interstate generates significant exposure for Madison on a daily basis. While traffic on Gallatin Pike has stagnated over time, I-65 traffic has nearly doubled over the same period, from around 60,000 in 1986. Clearly, regional north-south traffic is increasing (thanks in large measure to population growth in Sumner County), but commuters are choosing the interstate system over local roads and arterials.

Gallatin Pike is the region’s longest commercial corridor, extending more than 30 miles from the Cumberland River to Downtown Gallatin. Traffic and exposure for Madison is fairly high along Gallatin Pike. TDOT 2016 ADT counts on Gallatin Pike range from about 25,100 just south of Myatt Drive/Rivergate Parkway to 35,900 just north of Myatt Drive near RiverGate Mall. Gallatin Pike north of Briley Parkway has ADT of 32,300. In Downtown Madison (just south of Old Hickory Boulevard), Gallatin Pike has ADT of 27,900. These numbers all represent significant volumes for a local street and provide exposure for the commercial businesses that line this road. That being said, traffic counts have generally fallen over time since the 1980s, particularly around RiverGate Mall, and reduced traffic has impacted on business sales.

Briley Parkway is a major cross-town, limited access highway. The road carries 50,000 vehicles per day just east of I-65, with traffic increasing to 77,000 ADT each of Ellington Parkway and 87,800 ADT at the river. The interchange of I-65 and Briley has total traffic of about 212,000 vehicles per day generated by these two highways. Adding traffic from Ellington Parkway nearby brings the total to more than 260,000 vehicles per day. These combined interchanges may represent the busiest traffic node in Middle Tennessee, creating enormous potential exposure for Madison at this location.

Ellington Parkway carries 33,000 to 48,000 vehicles per day, which is comparatively modest number given that it is a limited-access highway that bypasses traffic on both I-65 and Gallatin Pike. Commuters have gradually noticed this advantage over time, and traffic on Ellington Parkway has increased by about one-third since the 1980s. South Graycroft Avenue, a local extension of Ellington Parkway towards the north, carries about 18,000 vehicles per day, which is relatively heavy for a two-lane local road. Other 2016 traffic counts generated by TDOT in Madison include the following:

- Old Hickory Boulevard: 20,000 (east of Gallatin) to 33,000 (west)

- Rivergate Parkway: 30,000

- Myatt Drive: 20,000-22,000

- Dickerson Pike: 13,000-21,000

- Conference Drive: 19,000

- Neely’s Bend Road: 11,000-14,000

- Due West Avenue: 13,000

- Anderson Lane: 5,000

- Alta Loma Road: 3,800

- Randy Road: 3,000

Bottlenecks and Congestion

Community members have identified issues with traffic volumes and bottlenecks, particularly at Neely’s Bend and Gallatin Pike, and within Downtown Madison. Improvements planned for the extension of Neely’s Bend (“Station Boulevard”) connecting to Old Hickory Boulevard are aimed in part at alleviating some of these congestion issues.

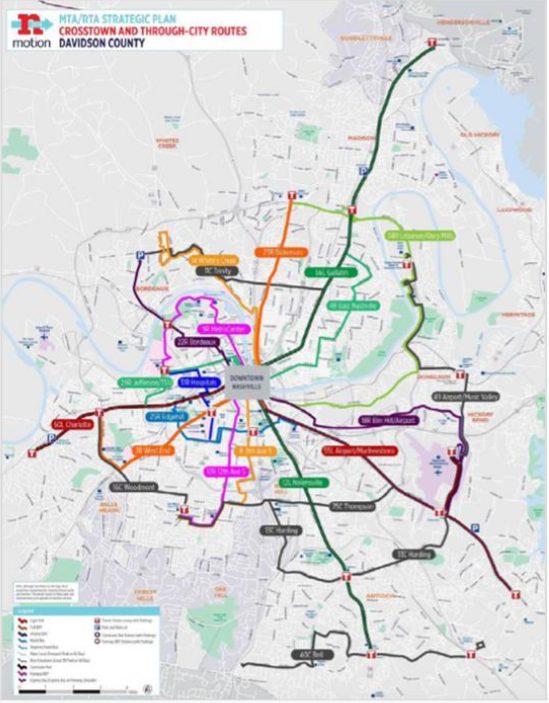

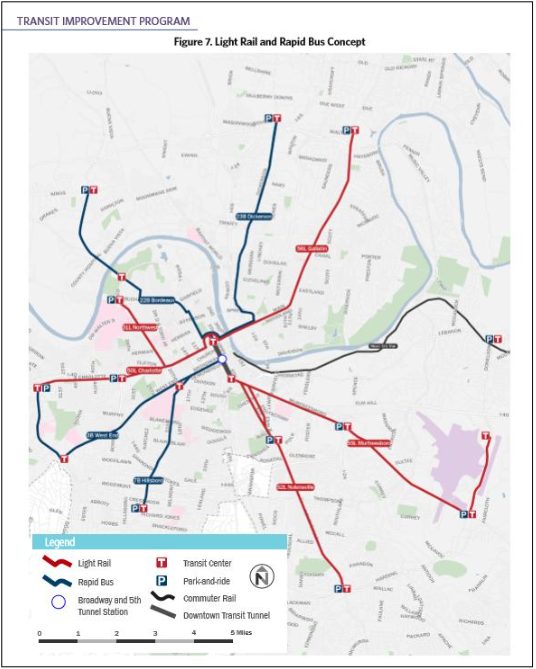

Public Transportation

Madison has good, well-utilized bus service including a BRT “Light” bus line along Gallatin Pike to Downtown Nashville. Bus routes 26 and 56 (BRT) provide direct service from Rivergate to Downtown. Other key routes include Route 76 through Neely’s Bend and Old Hickory Boulevard, Route 34 travels Briley Parkway and south on Ellington Parkway. The Route 36X bus from Downtown Madison travels south along Graycroft and connects to Downtown via Ellington Parkway. Route 27 connects Madison to Old Hickory and south to I-40. Meanwhile, routes 35X, 87X and 92X carry passengers south from Rivergate on I-65 towards Downtown Nashville.

The Gallatin Pike Corridor bus routes recorded 1,137,794 trips during 2017, the highest by far of any transit corridor in Davidson County. The next highest ridership was the Murfreesboro Pike Corridor, with 974,020 trips or about 15% less ridership than the Gallatin Pike Corridor.

Historical and Cultural Overview

The Madison area has a long and proud history separate from, and inter- connected with, that of the rest of Nashville. While the purpose of this Strategic Plan is not to document every detail from the rich history of Madison, it is important to discuss the highlights in order to provide context for understanding Madison today and to celebrate and strengthen its unique identity as we plan for the future. Unless otherwise noted, portions of the following historical overview is gleaned from information contained in the book, Madison Station, written by Guy Alan Bockmon and published by Hillsboro Press in 1997.

Natural Resources and Early Hunters

Before European settlement, the area that now comprises Madison provided a wealth of natural resources including salt “licks” along the Cumberland River that attracted herds of bison and other large mammals. Neely’s Lick was located at a sulphur spring, later named Larkin’s Spring after property owner Thomas Larkin. Larkin’s Spring became a popular place for bottling water in the early 20th century until Prohibition shut off the market for sulphur water as a “cure” for hangovers. Not surprisingly, the area became valuable hunting grounds for various early nations in this region, including the Cherokee. An area near the old Depot Lane (now Madison Street) has been identified as the possible site of an early American Indian settlement. Paths worn by bison (“Old Trailbreaker”), other large game animals, and early hunters gradually became trails for walking, hunting, and transportation by European American settlers with names like Mansker, Spencer, Buchanan, Craighead, and Love. Bockmon notes that busy Gallatin Pike originated as a humble bison path (“Old Trailbreaker’s Trace”) through virgin forests.

European Settlers

An early frontier outpost “Fort Union” may have been located near what is now Spring Hill Cemetery, and 18th century land grants subdivided huge areas near Love’s Branch (between Old Hickory Boulevard and McGavock Pike) for families including Scott, Cocke, Buchanan, McLean, Evans, Carvin and Dunham. Isaac Neely was another early settler, namesake for Neely’s Bend. Robert Hays, Thomas Overton, John Overton (Andrew Jackson’s law partner), and James Cole Montflorence joined a partnership for the manufacture of salt at Neely’s Lick. Violence reigned as settlers encroached on Cherokee hunting grounds. The Neelys’ daughter, Mary, was apparently taken prisoner by Cherokee around 1780, then escaped in Indiana disguised as a man and taken (again) as prisoner of war by the British. She later married George Speers and finally returned to Neely’s Bend in the 1840s.

Also in the 1780s, Presbyterian minister Thomas Brown Craighead led a group of about 20 families of Irish descent from Washington County, Virginia to preach and establish a church, and to build one of the region’s first schools (known as the Spring Hill Meetinghouse), located on the Buchanan land grant in Madison. Among the many contributors to Craighead’s school was Colonel James Robertson, a founder of Nashville. In 1806, the “Academy of Davidson County” was relocated from Spring Hill closer into Nashville and incorporated into Davidson College (later the University of Nashville). “Irish Station,” the community’s enclave, was located near Haysborough, just north of what is now Briley Parkway along the Cumberland River. A memorial to the Spring Hill Meetinghouse is located in the southwest corner of Spring Hill Cemetery.

Haysborough

In 1794, Colonel Robert Hays sold more than 300 acres along the Cumberland River. About 40 of those acres would be subdivided into 72 1⁄2-acre lots (each sold for $10). In 1802, the State General Assembly named Haysborough (later known as “Haysboro”) as an inspection point for hemp because it offered portage and harbor. By 1804, the village had about 20 houses. The first retail business in Madison, John Coffee’s Store (a “typical” country store), was established in Haysboro in 1802. Bockmon quotes Harriet Simpson Arnow in describing the “heady mixture of odors” emanating from the merchandise in this store:

The faint smell of dye and paste in the felt chip bonnets was all but smothered under the leathery, oily smell of new saddles and bridles; this in turn competing with the odors of New England cheese, vinegar, freshly broached keg of port or Madeira, and barrel of whiskey…chewing tobacco, ginger, nutmeg, mace and cloves.”

Frequent social activities like balls were held in town. At one point, there were three stagecoach lines operating through Haysboro, connecting it north to Louisville, Frankfort, and Lexington. But the village had already begun to stagnate by the 1810s. Davidson Academy relocated from the area in 1806. Competition increased from Methodists and Baptists to the area’s Presbyterian ministry. Flooding in the area in 1800 and 1810 may have reduced interest in Haysboro’s real estate. And the Nashville and Gallatin Turnpike Company opened its gates in 1839 on a route that bypassed Haysboro. By that time, the village only recorded about six families.

19th Civil District and the Civil War

The boundary of the old Davidson County Civil (Court) District 19 aligned somewhat with the southern half of the study area defined for this Strategic Plan: south along what is now Briley Parkway, west along Louisville Branch Turnpike (Dickerson Pike) and north along Dry Creek to the Cumberland River (which formed its eastern edge).

Thomas Stratton, a 27-year old planter from Powhatan County, Virginia, settled in what is now Madison in 1806. His son, Madison, would in turn bear the community’s name. Among the prominent citizens of the area at that time were Colonel Robert Weakley, David Vaughn, William Williams, and Samuel Love. Most of the planters in the area owned slaves: Willis Swann owned 180 acres and 5 slaves, Rueben Payne had 300 acres and 15 slaves, Edmund Goodrich had 400 acres and 9 slaves, while Peter Bashaw had 195 acres and 4 slaves. By 1840, the district was still a fairly sparsely-populated area of 1,065 people and an average farm of 248 acres. There were 442 slaves. The wealthiest man in the district was John Overton, with 1,200 acres and 27 slaves. In 1848, City Road Chapel began in a structure located near Old Hickory Boulevard and Gallatin Road. By 1850, the number of slaves had increased to 579, even though the overall population had fallen by 33 to 1,032. Over 90% of the district’s population was engaged in farming.

White men from these farms joined the “Cumberland Rifles,” C Company of the Tennessee Regiment in the Civil War. While Madison was not the scene of any major battles, its river, rail, and road assets were of paramount logistical importance to both sides and there were several skirmishes in 1862 near Neely’s Bend. Unlike other parts of Middle Tennessee, the 19th District’s farms remained relatively unscathed by the war, Edenwold and other antebellum homes intact. Most of these plantation homes were not demolished until the mid-20th century, such as when the Stratton home was razed for the construction of the Maybelle Carter

White men from these farms joined the “Cumberland Rifles,” C Company of the Tennessee Regiment in the Civil War. While Madison was not the scene of any major battles, its river, rail, and road assets were of paramount logistical importance to both sides and there were several skirmishes in 1862 near Neely’s Bend. Unlike other parts of Middle Tennessee, the 19th District’s farms remained relatively unscathed by the war, Edenwold and other antebellum homes intact. Most of these plantation homes were not demolished until the mid-20th century, such as when the Stratton home was razed for the construction of the Maybelle Carter

Retirement Center on Due West Avenue. “Glen Echo” was demolished for the entry ramp to Briley Parkway. “Evergreen” (located at 613 West Old Hickory Boulevard) may be among the only remaining antebellum-era homes in the Madison area.

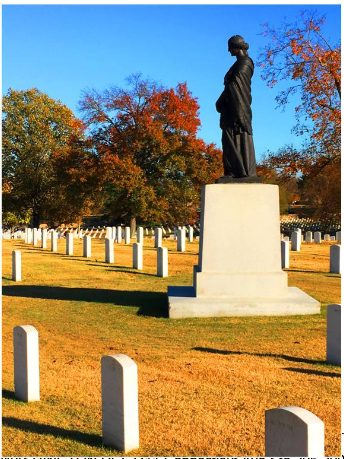

After the war, freedman in the 19th District tended to become sharecroppers on existing farms. In 1870, more than 98.4% of the area’s black residents were  illiterate, since they had not had access to education as slaves. In 1869, M.C. Meigs wrote that land alongside Gallatin Turnpike and the L&N Rail Line was selected as the location for a new National Cemetery “so that no one could come to Nashville from the north and not be reminded of the sacrifices that had been made for the preservation of the Union.” A total of 16,486 soldiers were interred at the cemetery, including 1,909 black soldiers who died fighting in the war.

illiterate, since they had not had access to education as slaves. In 1869, M.C. Meigs wrote that land alongside Gallatin Turnpike and the L&N Rail Line was selected as the location for a new National Cemetery “so that no one could come to Nashville from the north and not be reminded of the sacrifices that had been made for the preservation of the Union.” A total of 16,486 soldiers were interred at the cemetery, including 1,909 black soldiers who died fighting in the war.

Emerging Transportation Hub

When the area was mapped in the 1870s, Madison was still a rural area located along the Gallatin Turnpike, a dirt transportation route which extended from the village of Edgefield (now a neighborhood in East Nashville) to Gallatin, Tennessee. Over the years, Gallatin Pike has been known successively as Old Trailbreaker’s Trace, a bridle path, Avery Trace, Walton Road, Jackson Highway, the Nashville-Lexington Road, and U.S. Highway 31E. Other early roads in the area included Neely’s Bend, Hudson Lane, Goodrich Road (now Due West Avenue), Hall Lane, and Hamblen (now Campbell) Road. Until the 20th century, property owners were required to physically maintain the roads in front of their property or suffer fines. Several boats ferried people and animals across the Cumberland into what is now Donelson. Neely’s Bend Road was among the early east-west roads through the area and a creek (Craighead’s Branch) ran under what is now Briley Parkway.

Madison Station. The Edgefield & Kentucky Railroad (which later merged with the Louisville and Nashville (L&N) Railroad) extended parallel to both Gallatin Turnpike and Louisville Branch Turnpike (Dickerson Pike). In 1850, Madison Stratton sold land used for the construction of the station which bore his name, on level ground to accommodate trains on both the E&K and L&N lines. The Madison Station Post Office was chartered at the newly-opened station in 1857. Madison Station operated as a depot on the L&N passenger line until 1935 (when it closed despite the fact that the Madison Station may have been the most “prosperous” in the L&N system).”

Other stations were also built nearby along the rail lines: Ekin Station (located near Walton at the National Cemetery) was built after the Civil War and Amqui Depot (pictured here) was constructed in 1910. Tracks of the two rail lines (E&K and L&N) met at a place along Dry Creek known as Edgefield Junction (today about halfway between downtown Madison and Rivergate). While Madison had 100 residents in the 1880s, Edgefield Junction had 400 residents.

Other stations were also built nearby along the rail lines: Ekin Station (located near Walton at the National Cemetery) was built after the Civil War and Amqui Depot (pictured here) was constructed in 1910. Tracks of the two rail lines (E&K and L&N) met at a place along Dry Creek known as Edgefield Junction (today about halfway between downtown Madison and Rivergate). While Madison had 100 residents in the 1880s, Edgefield Junction had 400 residents.

An Interurban (trolley) line opened in 1913, connecting Downtown Nashville through Madison to Gallatin. Trolley lines were less expensive and more efficient for short commuter runs between the small towns and emerging urban neighborhoods around Nashville. Closed during the Great Depression, such lines could be considered a precursor to the “light rail” lines recently proposed along Gallatin Pike for future development.

Farms and Agriculture

After the Civil War, the average size of a farm in District 19 had fallen to just 59 acres. Despite growth in the number of farms, there were still 3,000 acres of woodlands around Madison Station in 1880. The Panic of 1873 (coupled with the cholera epidemic that followed) sent area farmers and their workers into an economic depression. Farm values fell precipitously and farm worker wages dropped to just $3.34 per week. After several years, agricultural production recovered in the area.

Even as late as the 1930s and ‘40s, Madison was comprised largely of farms and other agricultural enterprises. According to Bockmon, the area’s “mineral rich, loamy soil” and grasses helped support Madison’s many dairy farms producing milk and butter, as well as thoroughbred farming. Madison was part of the Bluegrass Region of Tennessee, which was as productive as Kentucky’s famous Bluegrass Region around Lexington. Pon’s bluegrass stock farm was a successful operation for many years. But strict religious dictates against gambling effectively killed the thoroughbred industry in Tennessee in the 19th century. W.O. Parmer’s Edenwold farm in north Madison was among the last great thoroughbred nurseries in Middle Tennessee. Madison’s Edenwold neighborhood derives its name from the old thoroughbred farm.

Commerce & Industry

As early as 1873, several business and institutional uses had clustered around what would become Madison Station, including Methodist and Presbyterian churches, Woodruff’s General Store, Sloan & Allen’s Marble Works, Baker’s Nursery, the “Little Red Schoolhouse,” and a small inn. Woodruff’s served as the community’s social center for several decades.

W.F. Gray relocated from North Carolina and opened the area’s first factory at the corner of Hall’s Lane and Gray Avenue in 1857. The company manufactured Gray’s Ointment (a highly successful cure-all and pain reliever), and propelled the company’s reputation as one of the oldest manufacturers in Tennessee, selling the “oldest remedy in the U.S.”

Grey’s concoction was made from turpentine, menthol crystals, pine tar, sassafras, carbolic acid, creosote, aluminum oxide, and zinc oxide. Sales spread throughout the nation through mail and parcel post delivery. The product was promoted by WWI soldiers as a cure for bunk lice: “Put on your old Grey’s Ointment…it burns and itches, but it kills those sons-a-…” The company was a fixture in Madison from 1860 through 1972, when its building was demolished for the Heritage House Apartments.

In the 1880 Census, area residents listed among their professions: farmers, laborers, tradesmen, servants, “hucksters,” fishermen, steamboat pilot, and banjo player. Immigrants began to arrive in the area from Germany, England, Scotland, Ireland, Prussia and Italy.

` Properties near Neely’s Bend Road and Madison Station were subdivided into smaller lots in 1880s and 1890s, suggesting the creation of a small unincorporated town. “Madison” at this stage had about 100 residents, a post office, doctor, justice of the peace, railroad agent, grocer, constable, live stock breeder, and dry goods store (Woodruff’s). As noted earlier, Edgefield Junction (which was later renamed Edenwold) expanded faster at first, with a grist mill, Roman Catholic & Baptist churches, 3 stores, and various service providers (blacksmith, telegraphers, carpenter, plasterer, wagonmaker, station agent, etc.

E. R. Doolittle acquired the Woodruff store in 1900, became Madison’s Postmaster and then started the community’s first bank – Madison Bank and Trust Company – in 1913. Doolittle helped form Madison’s Auxiliary of the American Red Cross to support the war effort in WWI. Also in support of America’s war efforts, the world’s largest powder plant was built and operated by the E. I. du Pont de Nemours Company across the river from Edenwold in Old Hickory. Madison served as a “bedroom community” to house some of the 17,000 workers who came to work at the massive plant, which received an average of 275 freight cars daily and frequent train service discharging workers at the Edenwold Ferry.

Real estate speculators helped construct Edenwold subdivisions with modest homes on streets named Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Scott (accidentally labeled “Scoot”) to support the workforce. Sometime later, houses were literally moved from Old Hickory to Madison.

Real estate speculators helped construct Edenwold subdivisions with modest homes on streets named Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Scott (accidentally labeled “Scoot”) to support the workforce. Sometime later, houses were literally moved from Old Hickory to Madison.

Davidson County tried unsuccessfully to gain federal Government funding to build a bridge from Neely’s Bend Road across to Hadley Bend (Old Hickory). Nevertheless a temporary pontoon bridge was constructed to ease traffic flow across to the plant. With the war over by 1919, the urgency of building a bridge was less apparent. The huge powder plant ceased operations, although by 1923, it was called back online as a private Du Pont chemicals facility. The Old Hickory Boulevard Bridge would finally be constructed over the Cumberland River by the end of the Great Depression.

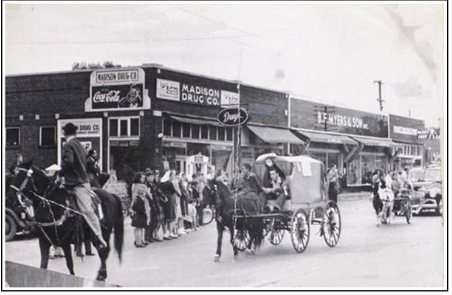

By the late 1930s, Madison had a number of businesses to serve its growing population base. Among those were the Stop & Shop grocery, Old Hickory Ice & Coal, Gamble’s Ford dealership, McClure Furniture, Doochin’s 5 & 10-Cent Store, Madison Bank & Trust, Piggly Wiggly, Lovely Pharmacy, Kornman’s Department Store, Hewitt’s Food Store, Meyer’s & Sons Department Store, Madison Theatre, Garrett’s Pharmacy, David Billiard & Pool Room, Armour’s Barber, Herndon Cleaners, Bill Vaughn auto dealer, McNish Lumber Yard and others. Madison Theater was described as a “handsome picture show house…Tennessee’s newest and most modern theatre.”

A “Madison Community Fair” was promoted in 1936 by the Madison News, a community newspaper that focused on social news and on clubs like the Civic Club, Big Brothers, Garden Club, Sewing Club, and various missionary and religious clubs. In 1941, the Odom family began producing and distributing sausage “loaded into an old Chevy, minus its back seat.” Madison’s Odom Sausage Company, home to “Tennessee Pride Country Sausage,” grew into one of the largest meatpacking operations in the South. The company began acquiring land in 1949 to build a large plant at 1201 Neely’s Bend Road. Few can forget the company’s famous advertising jingle “For real country sausage, the best you ever tried, look for me on the label of Tennessee Pride…Take home a package of Tennessee Pride!”

In 1953, local businesses formed the Madison Chamber of Commerce to boost the community’s growth, urging all businesses and professionals to join and “take an active part in helping Madison become the leading, modern town in the country.” A separate Neely’s Bend Chamber also operated for a while. The short-lived Madison Country Club was organized in 1945 and Tom Singer’s private Madison Airport began operations (including flying lessons) at the former (ca 1855) Smith Gee residence along the Cumberland River at Neely’s Bend Road in 1946. In 1948, Madison was promoted through the Nashville real estate board as “Nashville’s Largest Suburban Area, Population 8,000…The Pleasant City Out in the Country that Gives You a Cordial Welcome.” Madison was further promoted as being located at the center of a “prosperous bluegrass farming section… with clean air, bright homes, excellent modern stores…charming.” Horse shows were held at the Stratton School ring.

In 1953, local businesses formed the Madison Chamber of Commerce to boost the community’s growth, urging all businesses and professionals to join and “take an active part in helping Madison become the leading, modern town in the country.” A separate Neely’s Bend Chamber also operated for a while. The short-lived Madison Country Club was organized in 1945 and Tom Singer’s private Madison Airport began operations (including flying lessons) at the former (ca 1855) Smith Gee residence along the Cumberland River at Neely’s Bend Road in 1946. In 1948, Madison was promoted through the Nashville real estate board as “Nashville’s Largest Suburban Area, Population 8,000…The Pleasant City Out in the Country that Gives You a Cordial Welcome.” Madison was further promoted as being located at the center of a “prosperous bluegrass farming section… with clean air, bright homes, excellent modern stores…charming.” Horse shows were held at the Stratton School ring.

In 1954, Madison had two (community-supported) police departments, two banks, and two clinics, many grocery and dry goods stores, flower shops, shoe shops, hardware stores, drug stores, jewelry and novelty stores, three theaters (including a drive-in), and various other businesses like the popular Draper’s Home Supply Store.

Most urban services were funded through contributions from residents and businesses. Households each made $1 contributions per month through a “subscription service” to support the local police (added to the level of service provided by the County Sherriff) and were asked to cut and maintain the grass along streets in their neighborhoods. Despite the presence of added safety officers, Madison suffered some problems with crime and vice (bootlegging and gambling) after WWII. Businesses were asked to contribute to the cost of street lights along Gallatin Road (celebrated through a “Festival of Progress”) and the

Civic Club (later replaced by the Kiwanis Club) funded purchase of a fire engine for a new Volunteer Fire Department. Montague constructed its own fire station and space for a “teen town” activity center. A “Community Chest” was established to fund social causes. Still, the community lacked a sewerage system, traffic lights, sidewalks and curbs, business zoning laws, and other urban amenities and services.

Madison Square Shopping Center, one-third larger in size than the new Green Hills Shopping Center and “one of the largest in the south” was opened in 1956. A crowd enthusiastically estimated at 75,000 attended the grand opening, where the streets were paved with candy and pink poodles did tricks. However, significant new development was constrained until the new Dry Creek Sewerage Treatment Plant began operations in 1960. With adequate sewerage service, construction of large new apartment complexes, high rise retirement towers, hospitals, shopping centers, and malls with “their acres of paved parking lots” followed in the 1960s and 1970s. Construction of Interstate 65 accelerated suburban development not only into Madison but further north to Goodlettsville, Hendersonville, and beyond.

In 1962, county residents including those of Madison finally voted to join a Metropolitan Government to receive services as part of Nashville-Davidson County. Memorial Hospital (on Due West Avenue) became a major regional health care provider in Madison, until its function was replaced in the 1990s by the new TriStar Skyline Medical Center on I-65. Sale of the Memorial Hospital campus helped fund the Memorial Foundation, which continues to focus its resources on assisting the Madison and Greater Nashville communities.

Transition to Urban Corridor

With sewer service available, much of southern Madison was built out. Areas north of Dry Creek that had remained relatively rural until the 1960s saw increased residential development. The Gallatin Pike commercial corridor rapidly became known as the “Miracle Mile” (or “Motor Mile”) when dozens of car dealerships and associated automobile services were developed thanks to the availability of cheap commercial land with high exposure and access to emerging markets in Madison and Goodlettsville. The corridor was marketed regionally because of its concentration of auto retailers. In 1971, the Madison-Goodlettsville area and suburban Sumner, Robertson, and neighboring counties in Kentucky held sufficient population base to support the development of a super-regional shopping mall, Rivergate, with nearly 1.6 million square feet of commercial space and almost 200 stores. Development of Rivergate in turn spun-off substantial commercial strip development south along Gallatin Pike and west towards the new exit at I-65.

Rivergate become the primary commercial hub of Goodlettsville and Madison, north of Dry Creek. The mall helped capture a substantial share of the retail market that had once supported Downtown Madison. Development of I-65 also helped siphon off and redirect commuter traffic and market support from Downtown Madison. As a result, the traditional downtown area that had come to define Madison’s image and community heart for 100 years began to stagnate. The theater, tourist motels, and long-time retail stores closed and were replaced by discounters and lower-level service businesses. Madison’s older manufacturing concerns and national brands like Gray’s and Odom’s closed shop, but new industrial businesses arrived along the Myatt Drive Corridor. At least one historic structure – Amqui Station – was removed and restored by Johnny Cash, and later returned to Madison as a community asset.

As Nashville continued to expand outward, Madison became more akin to an urban neighborhood rather than a suburban bedroom community. The population gradually became more ethnically diverse as “white flight” drove middle-class families into Hendersonville, Gallatin, Mt. Juliet and other parts of Sumner or Wilson counties. Local schools in turn became less economically diverse and more dependent on school lunch programs to help families living below poverty level. Social service agencies and non-profit providers proliferated to help the growing population in need. Meanwhile, Madison retained much of its suburban, single-family housing stock and seemed to become two separate communities – one predominately white, aging and middle class; the other comprised of people of color or recent immigrants (especially from Mexico and Latin America), young, and working class. New institutions and assets, such as Nossi College of Art and the planned Madison Campus of Nashville State Community College, are helping to anchor Madison’s revitalization.

Madison Sanitarium and College

In 1904, missionaries from the Seventh Day Adventist Church arrived by boat at Larkin’s Spring and purchased 412 acres from W.B. Ferguson. They perceived Madison as “the wilderness.” The objectives of the Madison College were to establish a training school for evangelists and missionaries who would devote “their lives to the service of God and betterment of humanity.” By 1908, eight cottages housed 36 students.

In 1904, missionaries from the Seventh Day Adventist Church arrived by boat at Larkin’s Spring and purchased 412 acres from W.B. Ferguson. They perceived Madison as “the wilderness.” The objectives of the Madison College were to establish a training school for evangelists and missionaries who would devote “their lives to the service of God and betterment of humanity.” By 1908, eight cottages housed 36 students.

As part of the Adventist’s mission, the 12-room Madison Rural Sanitarium and Hospital was established with a revolutionary approach that offered patients “proper diet, fresh air, exercise, hydrotherapy, and a lot of kindness.”

Noted author (“Seven Times Seven”) and leader of the women’s suffrage movement Maria Thompson Daviess came to Madison for successful treatment at the Sanitarium and lived at Sweetbriar Farm (off Neely’s Bend Road), where she entertained “weekend assemblies of editors and illustrators (who) came down from New York and we all lived riotously.”

The church’s operations continued to grow and in 1931, the school acquired Madison Health Foods. Over the next several decades, the college’s reputation grew as it accepted applications from Africa, the Far East and South America and was granted four-year status by the State. An article about the college and sanitarium in Readers Digest helped the school attract 5,000 applications. With the addition of surgery and obstetrics in 1938, the medical facility became known as the Madison Sanitarium-Hospital. A leading Viennese doctor escaping Nazi persecution came to help direct the hospital’s operations. The campus’s fragrant gardens attracted tourists and visitors from throughout the region.

By 1954, the campus had expanded to a 220-bed facility. It continued to grow as part of the Tennessee Christian Medical Center. Eventually, however, both Madison College and the Sanitarium ran into financial difficulties and operations were severely reduced. However, the campus and other contributions of the Seventh Day Adventist Church remained embedded in Madison’s long- term legacy and the church’s regional headquarters remain in Madison today.

Suburban Development

The 1920s saw a brief era of real estate speculation that ended abruptly with the Great Crash of ‘29. The 48-lot Montague subdivision (bounded by Gallatin Pike, Gibson Creek, the river, and Belle Camp Highway (East Due West Avenue) was platted in 1919 and named for Montague Ross. Wealthy visitors used the 17 summer resort homes located along the river as the neighborhood expanded throughout the 1920s to include over 100 lots. The Madison Civic Club was formed to promote Madison in the early 1920s. The 188-lot Madison Park subdivision (Gallatin Road at Neely’s Bend) was advertised as a way to “invest in Nashville’s growth…and to grow with Nashville”. “Fast-growing” Madison itself was advertised to homebuilders as having many advantages including schools, churches, railway, train, and bus service.” The Douglas & Levine subdivision began sales in 1924. Madison Commerce Center was surveyed in 1926. The county’s first school bus may have run in Madison when the County paid Will Goodrich to transport children along Due West Avenue to Old Center School on Dickerson Pike.

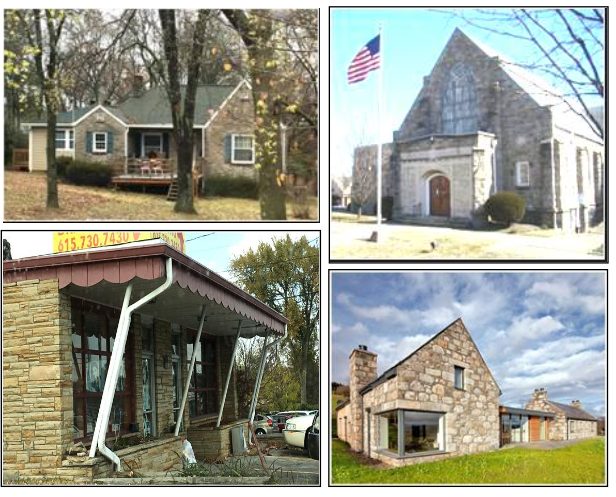

Newman Cheek (of the Maxwell House Cheek family) invested heavily in Madison’s growth, first with the development of his own estate “Sherwood Forest.” A WPA travel guide described it as “a private estate in which modern, rough-hewn limestone architecture reminiscent of the Victorian Gothic revival in England, is the dominant feature among grounds and gardens beautifully landscaped.” To supply water, Cheek built a lake that inadvertently covered the remains of Haysborough village. In order to provide a reliable water source for Madison’s development, the Madison Water Company was formed in 1927, soon to be replaced by the Lakewood Water Company. The Civic Club advertised Madison as “Nashville’s Premier Suburban Community.” By the 1930’s, “…much traffic passed through Madison at a high rate of speed, endangering the lives and property of pedestrians,” so the area’s first traffic light was installed.

Nawakwa Hills, Pawnee Trail and Forest Park subdivisions were surveyed and recorded, just as the Depression began, with elites looking for safe investments. The old Crittenden estate was proposed for subdivision and development of 206 lots (on Cherry, Oak, and associated streets). By the mid- 1930s, at least 3,000 people lived in Madison and 10,000 people lived in the combined suburban areas of Inglewood, Madison, Montague, Goodlettsville, and surrounding communities, and there was a fear that growth could be stunted if the water supply were to be cut off trough a failure at the source (Newman Creek). Further, only Goodlettsville had any fire protection. In 1937, Cheek persuaded the General Assembly to permit the incorporation of a public utility (Madison Suburban Utility District) that could purchase the Lakewood water utility and issue bonds without any other municipal government functions. With the start of WWII, suburban housing development came to a standstill in part due to the shortage of materials and manpower. Many of Madison’s finest enlisted in the war effort; plus nearly 40 joined the local Tennessee State (Home) Guard and another 30 became air raid wardens.

Pent-up demand allowed Madison, now a community of 7,000 people, to generate a post-war building boom starting in 1946. Developer J.R. Coarsey boasted “We believe in Madison – the finest and fastest-growing town in Tennessee.” Although their fear proved unfounded (at least for a decade), some Madisonians attempted to pre-empt any effort from Nashville to annex the community by seeking to incorporate. Coarsey, which developed the 45-lot Rainbow Terrace subdivision, noted that he expected Madison to triple in population within 10 years. Anderson Estates was subdivided by the Madison

Pent-up demand allowed Madison, now a community of 7,000 people, to generate a post-war building boom starting in 1946. Developer J.R. Coarsey boasted “We believe in Madison – the finest and fastest-growing town in Tennessee.” Although their fear proved unfounded (at least for a decade), some Madisonians attempted to pre-empt any effort from Nashville to annex the community by seeking to incorporate. Coarsey, which developed the 45-lot Rainbow Terrace subdivision, noted that he expected Madison to triple in population within 10 years. Anderson Estates was subdivided by the Madison

Real Estate Company north of Old Hickory Boulevard at the bridge in 1946. Coggin advertised home sites along Neely’s Bend Road to returning soldiers who could now afford to purchase homes through the G.I. Bill.

By the 1950s, Madison’s residential development could support 15 churches and 3 elementary schools (Neely’s Bend, Amqui, and Stratton (named after local education proponent John Taylor Stratton) plus Madison High School. “Hill Billy Day” was established as an annual festival and fundraiser for Stratton School. In its second year, the festival was already drawing crowds estimated at 50,000. Prior to the development of Madison High, local students attended Litton, DuPont, and Goodlettsville high schools. In 1947, Stratton was recognized for excellence by the Tennessee SesquiCentennial Committee through its distinguished Cordell Hull Award.

New development in the 1950s included Archwood Acres, Marlin Meadows, and others. However, a resolution to the sewerage issue became paramount to support continued growth. A public referendum was held in 1955 on the question of incorporation and solutions to the sewerage issue. At that time, Madison had a population of 11,200 and 175 businesses. The initiative failed due to concerns over the legalization of liquor stores and bars.

Music Heritage

Perhaps one of the earliest musicians to put Madison on the map was Joseph MacPherson, the first person to sing on radio station WSM, during the station’s  initial broadcast in 1925. Raised at the “old Ellis Place” in Madison and trained by teachers at Ward-Belmont, he went on to perform in Aida as a company member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York and also performed as a member of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville.

initial broadcast in 1925. Raised at the “old Ellis Place” in Madison and trained by teachers at Ward-Belmont, he went on to perform in Aida as a company member of the Metropolitan Opera in New York and also performed as a member of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville.

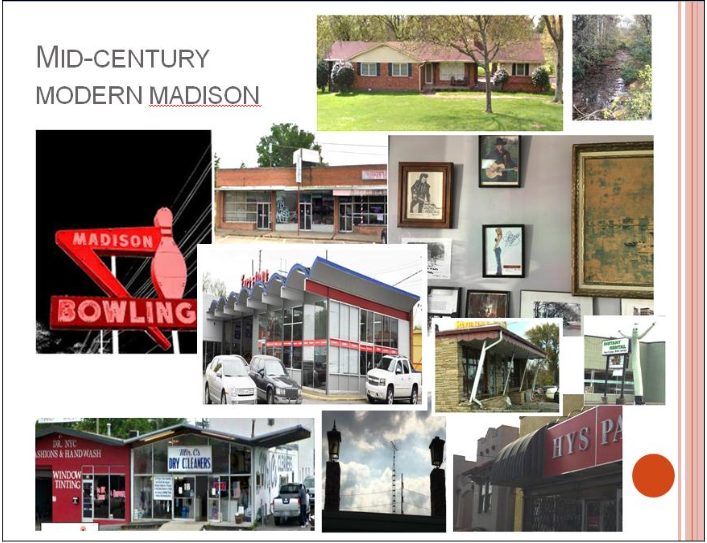

Nashville’s emerging prominence as a recording center and home to the “Nashville Sound” coincided with Madison’s residential boom in the 1950s and 1960s. As such, Madison attracted a number of recording artists to live and work in the suburb’s bright neighborhoods and attractive Mid-Century Modern homes.

Home of Maybelle Carter

Among the artists who established their residence in Madison during this era were Maybelle Carter, Kitty Wells & Johnny Wright, Eddy Arnold, Earl Scruggs, Everly Brothers, Charlie Louvin, Charlie Rich, Jon Hartford, Hank Snow, Loretta Lynn, Patsy Cline, Lester Flatts, Bashful Brothers, and others. A portion of East Old Hickory Boulevard has been renamed to honor Kitty Wells, the “Queen of Country Music.”

Elvis manager Colonel Tom Parker lived in a stone house on Gallatin Pike that also provided a recording studio and home-away-from-home for The King when Elvis came to Nashville. Virtuoso guitarist Wayne Moss has operated Cinderella Sound Studios out of his Madison garage for decades, producing such artists as Linda Ronstadt, Steve Miller Band, Kiss, Tony Joe White, Chet Atkins, The Whites, Billy Swan, and Memphis Slim, among others. Hank Snow’s Rainbow Ranch served as a recording studio and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Such luminaries as James Brown, Dottie West and Jim Reeves recorded at Starday-King Sound Studios, located on Dickerson Pike.

Elvis manager Colonel Tom Parker lived in a stone house on Gallatin Pike that also provided a recording studio and home-away-from-home for The King when Elvis came to Nashville. Virtuoso guitarist Wayne Moss has operated Cinderella Sound Studios out of his Madison garage for decades, producing such artists as Linda Ronstadt, Steve Miller Band, Kiss, Tony Joe White, Chet Atkins, The Whites, Billy Swan, and Memphis Slim, among others. Hank Snow’s Rainbow Ranch served as a recording studio and is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Such luminaries as James Brown, Dottie West and Jim Reeves recorded at Starday-King Sound Studios, located on Dickerson Pike.

Madison continues to host musicians, home recording studios, and popular live music venues like Larry’s Grand Ole Garage, Lonnie’s Bluegrass Festival, and Dee’s Country Cocktail Lounge.

Madison continues to host musicians, home recording studios, and popular live music venues like Larry’s Grand Ole Garage, Lonnie’s Bluegrass Festival, and Dee’s Country Cocktail Lounge.

Economic Overview

While part of Metro Nashville, Madison has long had a strong economic identity of its own. As noted previously, Madison has served as the headquarters and manufacturing hub for companies like Odom’s (meatpacking) and W.F. Gray (remedies). Du Pont operated the world’s largest powder plant and later, major chemicals manufacturing facility, just across the river in Old Hickory. And Dollar General Stores, the nation’s 2nd largest discount general merchandise store chain, is headquartered just north of Madison in Goodlettsville. A number of manufacturing and distribution companies continue to operate in Madison’s Myatt Drive Corridor, and newcomers like Diamond Gussett Jeans and Yazoo Brewing are bringing new manufacturing jobs to Madison. Others are working on adding entrepreneurial space for light manufacturing and small batch producers.

Madison has been home to two hospitals – Memorial and Tennessee Christian (formerly Madison Sanitarium) – and HCA Skyline Medical Center is located on the south-western rim of Madison today. Several colleges, including the planned campus of Nashville State Community College, have called Madison home. Metro Government facilities include a new $40 million, 82,500 square-foot facility at 400 Myatt Drive housing a state-of-the-art crime lab, the Madison Police Precinct, and a 5,800 square-foot community meeting venue. Adjacent to this new facility are the Headquarters for the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA). Situated along the region’s longest commercial corridor, Madison has long had a substantial retail/commercial base including major regional shopping nodes at Madison Square and RiverGate Mall. The “Motor Mile” attracted large automotive dealers to the area. But the area has also had a long history supporting small businesses, musicians, tradesmen, and entrepreneurs.

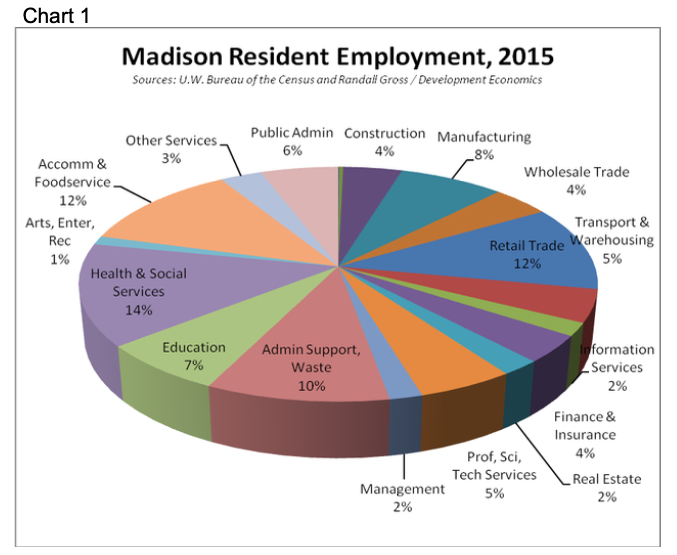

Resident Labor Force

Madison’s residents are employed in a variety of jobs throughout the region. Based on 2015 Census data, a total of 17,600 Madison residents are employed in a diverse set of industries covering all major sectors. The largest share of residents is employed in health & social services (14%), followed by accommodation & foodservice (hospitality, 12%), retail trade (12%), manufacturing (8%), education (7%), and public administration (6%). But Madison’s residents work in a number of other sectors as well. The diversity of the community’s workforce skills is illustrated in the chart below.

Commutation. Today, a significant share of Madison residents works in Madison (e.g., RiverGate), but many more commute to jobs throughout the Nashville Metropolitan Area. Based on U.S. Census data, high concentrations of Madison’s residents commute to work in Midtown (e.g., Vanderbilt Medical Center and other hospitals), Donelson (Opry Mills, Nashville International Airport), East Nashville, Brentwood, and southeast Nashville’s industrial corridor. Since a large number of Madison’s residents work for Metro schools, as contractors, or within the hospitality industry, they commute to a variety of locations throughout Davidson County. A surprisingly small share of Madison’s residents works in Downtown Nashville.

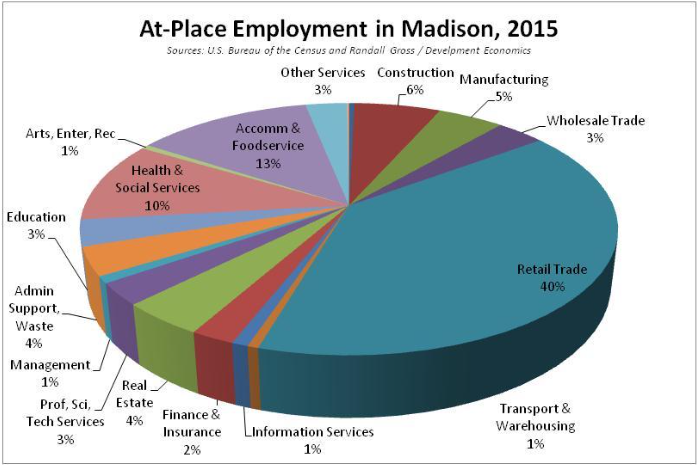

Employment in Madison

There were about 11,400 jobs located in Madison in 2015. The employment base in Madison is heavily oriented to retail trade, which comprises 40% of all jobs in the community. Most of this employment is concentrated in RiverGate Mall and in shopping centers located along the Gallatin Pike corridor. Another 13% of Madison’s jobs are in accommodation and foodservice, mainly in fast food and full-service restaurants. So together, more than half of all jobs in Madison are concentrated in the retail/commercial sector. If Madison were an independent municipality, this dependency on relatively low-wage retail jobs would pose a serious risk to the local economy.

Health and social services account for another 10% of jobs, such as in medical clinics and physicians’ offices, social service agencies and in positions associated with Skyline Medical Center.

The remaining jobs in Madison are distributed among a variety of other industry sectors. For example, construction accounted for 6% of Madison’s jobs, manufacturing 5%, etc.

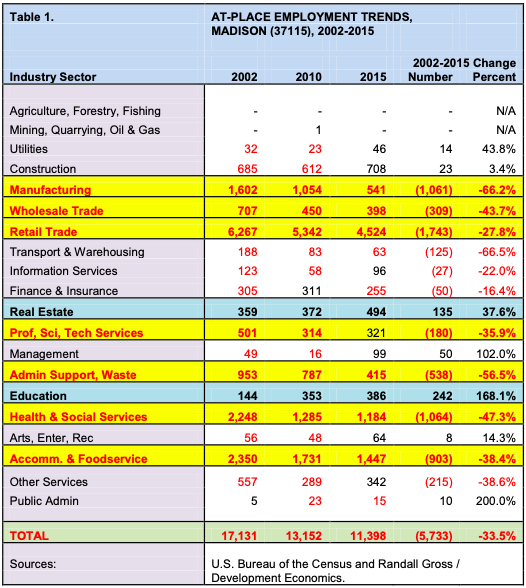

Employment Trends. Madison’s employment base has fallen by 5,700 or one-third since 2002. Most of that loss occurred through the national recession by 2010, but the community has continued to lose jobs since the recession ended. The largest job losses were in retail trade (1,740), health & social services (1,060), manufacturing (1,060), and accommodation & foodservice (900). The fastest-declining industries were manufacturing (where Madison lost nearly two-thirds of its manufacturing jobs), administrative support (57%), health & social services (47%), and wholesale trade (44%).

Despite the losses, a few industries have been growing in Madison. The education sector added over 240 jobs and real estate added 140. There has also been a slight turnaround in some sectors that had seen declining employment between 2002 and 2010 but are now experiencing growth. For example, the construction sector lost jobs during the recession but has gained nearly 100 jobs since 2010. The arts, utilities, information services, management services and other services have seen increasing employment since the end of the recession. Overall employment trends are summarized in the following table.

A key issue has been retention of good-paying jobs for residents of Madison and nearby communities, as employment has fallen in manufacturing and other sectors.

Baseline Demographics

A demographic analysis was conducted of Madison in 2016 (based on 2014 data) as part of the initial baseline work for this Strategic Plan. This data was recently updated for the U.S. Census Tracts that comprise Madison.

Population and Households

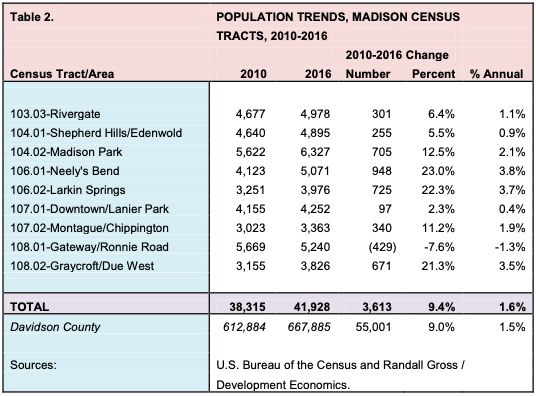

Based on these Census estimates, Madison has a total population of nearly 42,000, up by more than 3,600 or 9.4% since 2010. Madison represents 6.3% of Davidson County’s total population.

Madison’s population has increased at a rate of 1.6%, slightly faster than Davidson County’s as a whole. This is a remarkable achievement, given that Madison is a relatively built-out section of the county. All of the tracts within Madison experienced an increase in population in recent years with the exception of Tract 108.01, which includes portions northeast of the intersection of Old Hickory Boulevard and Gallatin Pike (south of Rivergate). It is possible that some of the single-family homeowners in this area are aging and becoming empty nesters, with smaller households, or are moving out of the area.

Overall, the nine census tracts in Madison surprisingly retain about the same number of residents, between 4,000 and 6,000, so the population is relatively evenly distributed throughout the community. The fastest population growth has been in the southern Neely’s Bend area (23.0% in just six years) and areas closer into Downtown Madison near Larkin Springs (22.3%). Neely’s Bend also added the largest number of residents, at nearly 1,000 (and areas near Larkin Springs added more than 700). This growth is not surprising, given that these areas are among the more rural and less-developed in Madison. The Graycroft area near Due West Avenue has also experienced fairly rapid growth, with a 21.3% increase in population. The area closer to Downtown Madison added only about 10 residents per year since 2010.

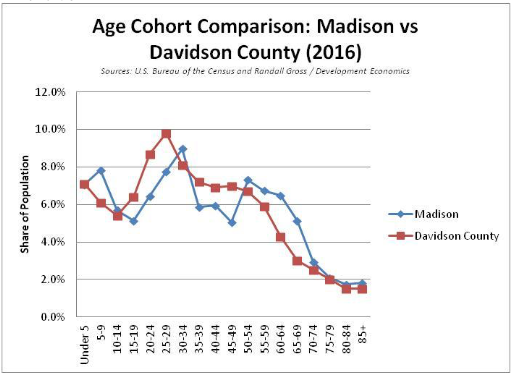

Age Cohorts. Madison’s population was also examined by age cohort, as an important indicator of both market demand and need for housing and various services. Madison’s population is fairly evenly spread among all 5-year age cohorts, up to the age of 70. Each of these age cohorts generally has between 5 and 7% of Madison’s population. So, there is no one age group that dominates the community. The only age cohort for which there is somewhat more represented than others is the 30 to 34 age group (part of the so-called “Millennial” generation), in which about 9.0% of Madison residents reside. Madison’s population-by-age spread was compared with that of Metro Nashville as a whole in the following chart.

As shown above, Madison tends to have a smaller share of its population in the 15-29 and 35-49 age cohorts, but has a larger share aged 50 and above. A comparison of key life stage age cohorts is shown below.

| Life Stage | Madison | Davidson County |

|---|---|---|

| Children (0-19) | 25.7% | 25.0% |

| Young Adults (20-39) | 29.0% | 33.8% |

| Mid Age (40-69) | 36.7% | 33.8% |

| Senior (70+) | 8.6% | 7.5% |

Young adults represent a smaller share of Madison’s population than in the rest of the county, while Madison has a higher share of both mid-age and senior populations. This finding is not surprising, given that Madison provides a more suburban, “settled” location with a large number of single-family homes. As the Millennial generation ages into families with children, they are becoming more likely to settle in communities like Madison that offer affordable single- family housing options proximate to employment.

Among the various neighborhoods in Madison, Children are more highly represented in Madison Park, Larkin Springs, and Gateway/Ronnie Road. Young Adults are found as a higher share in Rivergate, Downtown/Lanier Park, and Madison Park. Mid-age populations are found in higher shares in Neely’s Bend, Graycroft/Due West, and Rivergate. Finally, seniors represent a higher than average share of the population in Montague/Chippington and Graycroft/Due West (where nearly one in five is over the age of 70).

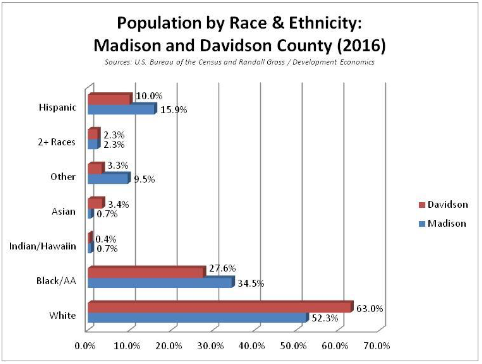

Race and Ethnicity. A slight majority (52.3%) of Madison’s population identifies as white. In general, Madison is somewhat more racially and ethnically diverse than the rest of Davidson County as a whole.

About 34.5% of Madison’s population is black or African-American, versus 27.6% countywide. Madison also has a slightly larger share who identify as American Indian or Hawaiian, but a much smaller share who identify as Asian (0.7% versus 3.4% countywide). A much higher share of Madison’s residents identify with races other than those posed by the Census Bureau’s list.

Madison also has a larger share of residents who identify as Hispanic or Latino, at nearly 16.0% in 2016, up from 12.0% in 2010. This compares with a growing but still smaller share countywide of 10.0% (up from 9.0% in 2010). Those who identify as Hispanic or Latino as an ethnicity can identify with any race, so they are also included in the race categories.

Madison’s Hispanic population is fairly well concentrated in certain areas, including Downtown/Lanier Park (where Hispanics represent nearly 26% of the population), Madison Park (24%), Montague/Chippington (24%), and Shepherd Hills/Edenwold (22%). By contrast, only about 2% of the Rivergate area and 5% of the Graycroft/Due West area population identifies as Hispanic.

Foreign-Born. Madison has an estimated 4,100 foreign-born residents, which represents about 5.0% of Davidson County’s total. Of this number, 85% (3,430+) are estimated to originate from Latin America. Another 370 (9%) are from Asia, and the rest from Africa (160), Europe (60), and North America (30). This population contributes to and strengthens the cultural diversity of Madison and helps to create a workforce available for the community’s growth.

Distressingly, roughly 85% or 3,470 of Madison’s immigrants have not been naturalized as U.S. citizens. While many reside legally as U.S. residents, all are subject to uncertainties regarding their status within the current political climate. Having more than 8.2% of the community’s population living with such uncertainty can impact negatively on the community’s schools, business base, and housing market.

Education

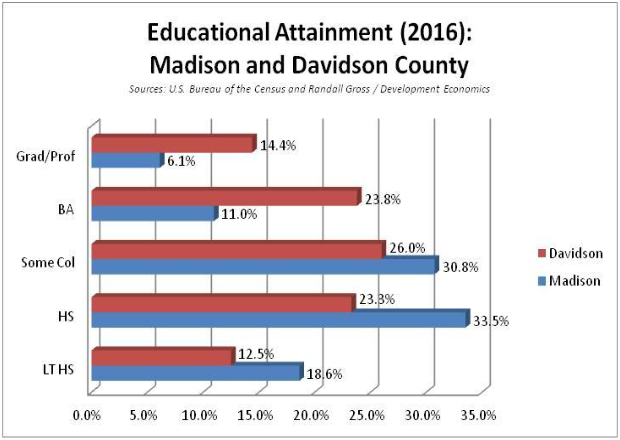

On average, educational attainment among adults 25 and older is lower in Madison than in Nashville as a whole. For example, Census estimates suggest that 14.4% of Nashvillians have attained a graduate or professional degree, but only 6.1% of Madison residents have done so. Almost 24% of adult residents countywide have attained a bachelor’s degree, but only 11% of Madison’s adults have attained a BA or BS degree. By the same token, nearly 19% of Madison adults have less than a high school education, while less than 13% of adults countywide have not graduated from high school (or achieved its equivalent). Most adults in Madison have achieved either a high school degree (33.5%) or have attended some college or received an associates’ degree (30.8%). The following chart illustrates this comparison.

Educational achievement is not uniform throughout Madison. For example, more than 30% of adults in the Graycroft / Due West Avenue area of southwest Madison have received either a BA or graduate degree. Only 5.7% of Madison Park area adults have achieved these degrees. Meanwhile, more than 30% of adult residents in the Shepherd Hills/Edenwold area of northeast Madison have less than a high school education.

Educational achievement is not uniform throughout Madison. For example, more than 30% of adults in the Graycroft / Due West Avenue area of southwest Madison have received either a BA or graduate degree. Only 5.7% of Madison Park area adults have achieved these degrees. Meanwhile, more than 30% of adult residents in the Shepherd Hills/Edenwold area of northeast Madison have less than a high school education.

Income & Poverty

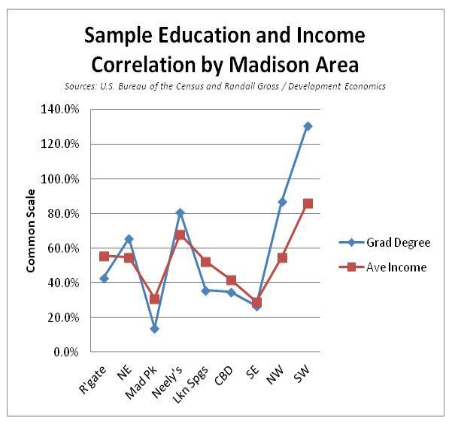

There is often a correlation between education levels and incomes (as illustrated in the sample comparing average household incomes with the share having graduate degrees, at right).

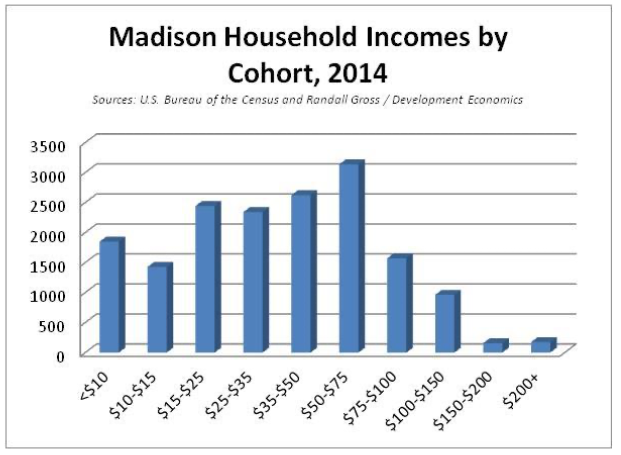

Madison incomes, like its education levels, trail behind countywide averages. The community’s estimated median income (2016) was $38,276, or just 75.8% of the countywide median of $50,484. And Madison’s average household income of $48,269 was only 66.5% of the countywide average of $72,553. Households by income cohort are shown below (using 2014 data).

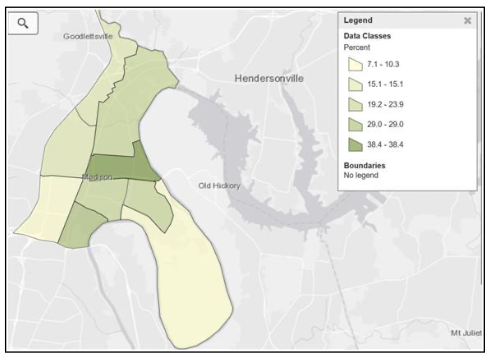

Madison has a somewhat higher poverty level, at 20.4%, than Davidson County as a whole (17.7%), according to the 2016 Census estimates. Within Madison, poverty tends to be concentrated in certain areas. For example, fully 38.4% or nearly four out of ten Madison Park residents live below the federal poverty level. About 29.0% of the residents in southeast Madison (which includes Chippington Towers) live below the poverty line. And, 24% of residents in Downtown Madison and Lanier Park live in poverty. By comparison, only 7.1% of Neely’s Bend residents live below poverty levels as shown below.

Here it is apparent that Madison has a cluster of households earning incomes within the lower and lower-middle ranges ($15,000 to $75,000), which would be expected for households led by someone who has achieved a high school degree. There is also a number of households with incomes of less than $15,000, which constitutes the householders living below poverty levels. But there are relatively few Madison households with incomes above $75,000, and fewer still earning more than $150,000 per year. Again, education certainly impacts on Madison’s income levels, along with other factors such as the age of householders.

Site Analysis

A site analysis was conducted to examine the existing location, physical characteristics, assets and other features of Madison that impact on its overall marketability and on opportunities for celebrating its unique identity and community. Some key findings from the site analysis are summarized below, with more detail on existing retail, residential, office, and industrial uses provided within the findings from the respective market analyses in the Part B Report.

Cultural and Historical Assets

Madison has a large number of cultural and historical assets. Among the historic assets are the restored Amqui Railroad Station and National Cemetery, as well as various sites associated with Madison’s music and religious heritage.

Madison has a large number of cultural and historical assets. Among the historic assets are the restored Amqui Railroad Station and National Cemetery, as well as various sites associated with Madison’s music and religious heritage.

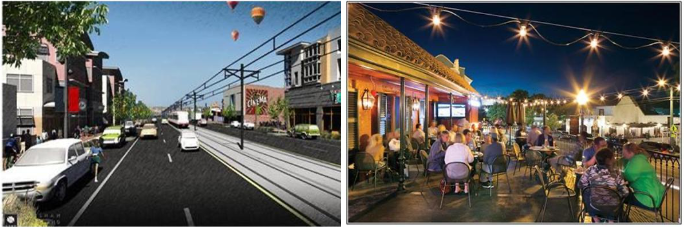

Music-related sites in Madison include the former homes of Maybelle Carter, Kitty Wells & Johnny Wright, Eddy Arnold, Earl Scruggs, the Everly Brothers, Charlie Louvin, Charlie Rich, Jon Hartford, Hank Snow, and others involved in developing the “Nashville Sound.” Other key music-related sites have unfortunately been demolished, such as the home of Colonel Tom Parker (Elvis’s manager). Wayne Moss’s Cinderella Sound Studios is still operating in Madison as is Larry’s Grand Ole Garage Bluegrass Music Park, joined more recently by Dee’s Country Cocktail Lounge. Working musicians throughout Madison continue to maintain studios in the area.

Wall mural in Madison illustrating a village scene in Latin America. Madison has relatively few of these murals or other celebrations of the community’s cultural diversity. But Madison offers many potential opportunities for cultural expression, given its increasingly diverse population and immigrant base, educational institutions including an art college (see below), churches, and other assets.

Educational and Institutional Assets

The new Madison Branch Public Library, Madison Police Precinct Headquarters, a Regional Community Center, MTA Headquarters, and the recently-opened Madison Community Center illustrate government assets located in Madison.

Educational institutions are also important assets for the community, including public and charter elementary, middle and high schools. More detailed information on area schools is provided later in this section. Several colleges in Madison can serve as anchors for revitalization and investment. Among the colleges are Nossi College of Art, Middle Tennessee School of Anesthesia (part of the Madison Adventist Campus), Nashville College of Medical Careers, and the planned new Nashville State Community College.

Educational institutions are also important assets for the community, including public and charter elementary, middle and high schools. More detailed information on area schools is provided later in this section. Several colleges in Madison can serve as anchors for revitalization and investment. Among the colleges are Nossi College of Art, Middle Tennessee School of Anesthesia (part of the Madison Adventist Campus), Nashville College of Medical Careers, and the planned new Nashville State Community College.

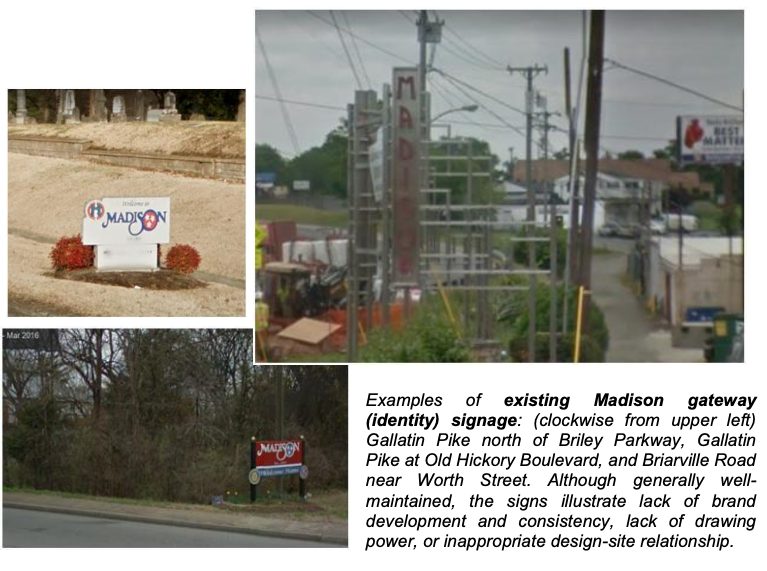

Madison’s churches play an important role not only in the spiritual health of the community but also as service providers and through outreach to those that need help in the community.